Key Knowledge:

|

A disease is a condition that disturbs the normal physiology of the body, leading to a deterioration in the state of health (illness)

- An infectious disease is caused by a transmissible agent called a pathogen that disrupts the body's homeostatic processes

Pathogens

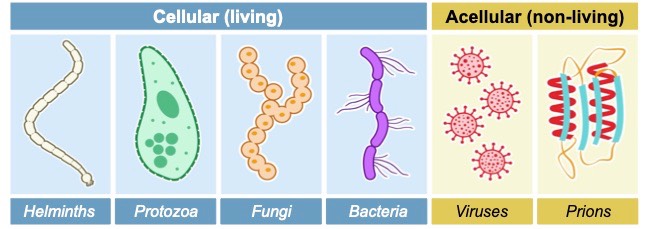

A pathogen is a disease-causing agent that can either be cellular (living) or non-cellular (non-living)

- Examples of cellular pathogens include parasites, protozoa or bacteria, while non-cellular pathogens include viruses and prions

Non-Cellular Pathogens

Non-cellular pathogens cannot reproduce independently and spread infection via protein isoforms (prions) or via nucleic acids (viruses)

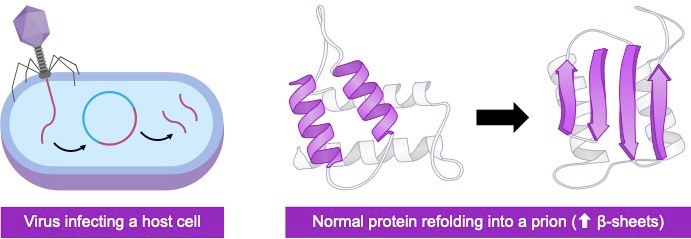

Viruses

- Viruses are submicroscopic agents that commandeer cells to rapidly propagate new virus particles (virions), preventing homeostasis

- Viruses are metabolically inert and are incapable of reproducing independently of a host cell (hence are non-living)

- They typically consist of an inner core of nucleic acid surrounded by a protein coat (capsid)

- Simpler viruses may lack a capsid (viroids), whilst more complex viruses may possess an external lipid envelope

- Viruses can be either DNA-based adenoviruses or RNA-based retroviruses (which require reverse transcriptase to make DNA)

- Viruses can integrate into a host genome and remain dormant for a period while the infected cell replicates (lysogenic cycle)

- Viruses may also destroy the host cell in order to spread new virus particles (lytic cycle)

Prions

- A prion is an infectious protein that has folded abnormally into a structure capable of causing disease

- Prions can cause normally folded proteins to refold into the abnormal form and hence propagate within a host body

- Prion proteins aggregate together to form amyloid fibres that cause holes to form in the brain (spongiform encephalopathy)

- Infectious prion proteins have a higher beta-sheet content, making them more resistant to denaturation and difficult to treat

Cellular Pathogens

Cellular pathogens function as parasites – growing and feeding on another organism without contributing to the survival of the host

- They can either live on the surface of a host (e.g. moulds, arthropods) or within the host tissue (e.g. bacteria, protozoa, helminths)

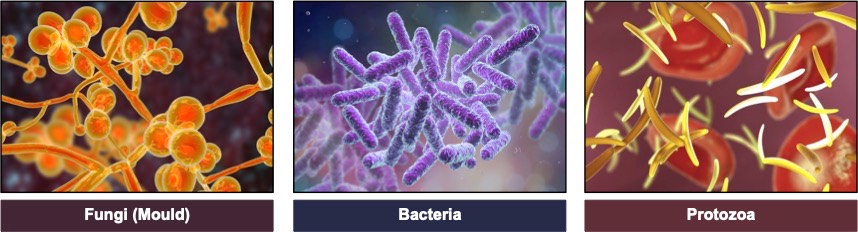

Fungi

- Fungi usually colonise body surfaces (skin or mucous membranes) and can be unicellular (yeasts) or multicellular (moulds)

- Moulds consist of filaments called hyphae, which may trigger disease by forming a mass of invading threads called mycelium

- Examples of fungal infections include thrush (yeast infection) and athlete’s foot (mould infection)

Bacteria

- Bacteria are unicellular prokaryotic cells that can reproduce quickly and compete with host cells for space and nutrition

- Most bacteria are relatively harmless and some may even form mutualistic relationships with hosts (e.g. normal gut flora)

- Bacteria may cause disease by producing toxic compounds (exotoxins) or releasing the substances when destroyed (endotoxins)

- As the toxins retain their destructive capacity beyond bacterial death, they are often the cause of food poisoning

Other Examples

- Ectoparasites live on the surface of a host and may cause disease in humans either directly or indirectly

- Arthropods (lice, ticks and mites) feed on the blood and may directly cause disease by injecting substances that act as toxins

- Insects (fleas and mosquitoes) may not have an inherently harmful bite but may indirectly cause disease by acting as a vector

- Endoparasites live within hosts and include microparasites (e.g. unicellular protozoa) or macroparasites (e.g. multicellular helminths)

- Examples of protozoa which cause disease include Plasmodia (malaria) and Trypanosoma (African sleeping sickness)

- Examples of helminth which cause disease include roundworm, tapeworm and flatworm (note: 'ringworm' is a fungal infection)

Pathogen Identification

Most multicellular organisms possess some form of intrinsic immune system to allow them to respond to pathogenic infections

- The immune system can differentiate betwen foreign (non-self) and native (self) cells due to the presence of identification markers

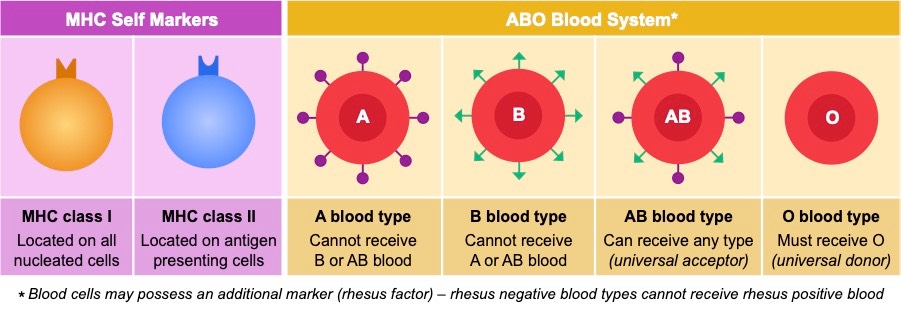

Self Markers

All nucleated cells in the human body possess distinctive surface molecules that serve to identify the cells as part of the host (self)

- These self markers are called major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules and are unique to the host organism

- The immune system will not normally react to cells bearing these genetically determined markers (i.e. self tolerance)

- As these markers are unique to the host, the MHC molecules from different organisms will initiate an immune response

- Closely related individuals will have genetically similar markers and be less likely to reject donor tissue from organ transplants

Red blood cells are not nucleated and hence do not possess MHC markers (so can potentially be transferred without rejection)

- Red blood cells do possess basic selection markers (the ABO blood system) which limit the capacity for universal transfusions

- Only individuals that possess a common or compatible blood group will be able to exchange blood without immune rejection

Antigens

Pathogens will possess certain common molecular markers that the immune system can recognise and respond to non-specifically

- These molecular characteristics are called pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and initiate an innate immune response

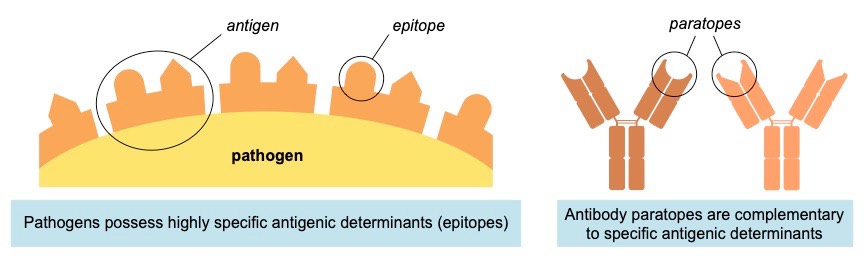

Pathogens additionally possess distinctive molecular fragments that the immune system can recognise and respond to specifically

- These particular substances that are recognised as foreign and elicit a specific immune response are called antigens

Antigens are recognised based on the characteristic shape of an exposed portion of the molecule called the epitope

- The immune system produces specific antibodies that bind to the epitope via a complementary paratope (antigen binding site)

- Antibodies are a class of proteins (called immunoglobulins) that neutralise pathogens by targeting their antigenic determinants

Allergens

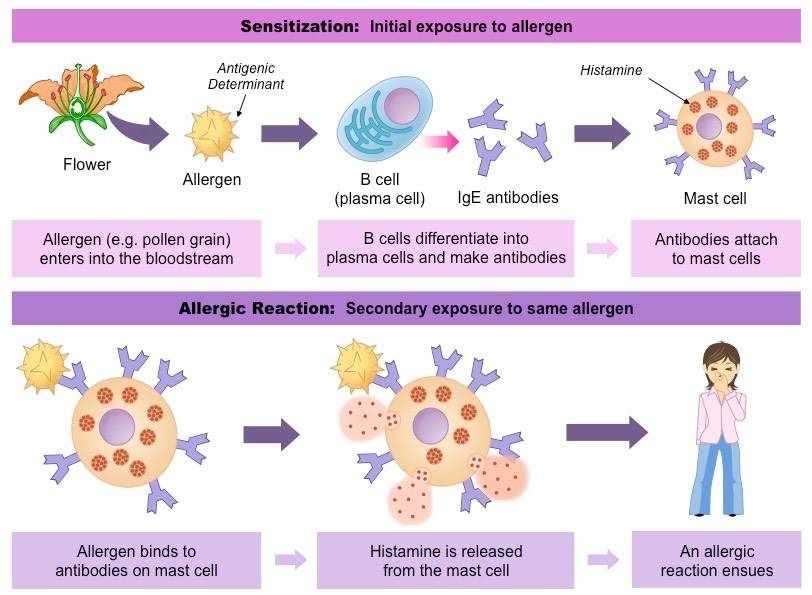

An allergen is an environmental substance that triggers an immune response despite not being intrinsically harmful

- This immune response tends to be localised to the region of exposure (e.g. airways and throat) as an allergic reaction

- A severe systemic allergic reaction is called anaphylaxis and can be fatal if left untreated

An allergic reaction requires a pre-sensitised immune state (i.e. prior exposure to the allergen)

- Upon initial exposure to an allergen, specific antibodies (IgE) are produced that attach to particular immune cells (mast cells)

- The antibodies effectively ‘prime’ the immune system towards the allergen, resulting in a hypersensitive response upon re-exposure

- IgE-primed mast cells trigger an allergic reaction by releasing large amounts of histamine which causes inflammation