Key Knowledge:

|

The central dogma of molecular biology explains the flow of genetic information within the cell (i.e. DNA → RNA → Protein)

- DNA codes for RNA via the process of transcription (occurs within the nucleus of eukaryotic cells)

- RNA codes for protein via the process of translation (occurs at free ribosomes or at the rough ER)

While this information flow is typically unidirectional, certain viruses can convert RNA into DNA via the enzyme reverse transcriptase

Genes

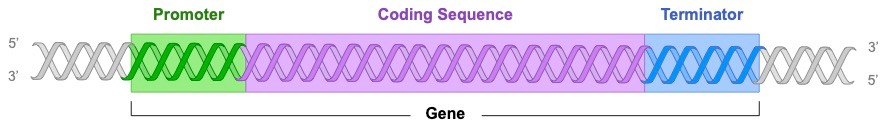

A gene is a sequence of DNA which is transcribed into RNA and contain three main parts:

- Promoter: A sequence that serves to initiate transcription – acts as a binding site for the transcribing enzyme (RNA polymerase)

- Coding Sequence: The sequence of DNA that is actually transcribed into RNA (may contain non-coding introns in eukaryotes)

- Terminator: The sequence that serves to terminate transcription (mechanism of termination differs in prokaryotes and eukaryotes)

Genes can be located on either of the two strands of DNA, allowing for the compact organisation of a cell’s genetic instructions

Transcription

Transcription is the process by which an RNA sequence is produced from a DNA template

- RNA polymerase binds to the promoter and triggers the unwinding and separation of the DNA strands

- When the DNA strands are separated, free RNA nucleotides will align opposite their complementary base partner

- RNA polymerase then moves along the coding sequence and covalently joins the RNA nucleotides together

- At the terminator, RNA polymerase and the newly formed RNA strand both detach from the DNA template, and the DNA rewinds

- Many RNA polymerase enzymes can transcribe a DNA sequence sequentially, producing a large number of transcripts

RNA Processing

In eukaryotic cells, the RNA transcripts must first be processed in order to form mature messenger RNA (mRNA)

This processing assists in the nuclear export of the transcript and facilitates its recognition by translational machinery (ribosomes)

Examples of post-transcriptional processing include:

- Capping: A methyl group is added to the 5’-end of the transcript to protect against degradation by exonuclease

- Polyadenylation: A long chain of adenine nucleotides (a poly-A tail) is added to the 3’-end to improve the stability of the transcript

Additionally, eukaryotic genes contain non-coding sequences called introns, which must be removed prior to forming mature mRNA

- Introns are intruding sequences within a gene, whereas the protein-encoding regions are called exons (i.e. expressing sequences)

- When the introns are removed, the exons are fused together to form a continuous sequence that can then be translated

- The process by which introns are removed is called splicing (prokaryotic genes do not have introns and so do not require splicing)

Splicing can also result in the removal of exons – a process known as alternative splicing

The selective removal of specific exons will result in the formation of different polypeptides from a single gene sequence

- For example, a particular protein may be membrane-bound or cytosolic depending on the presence of an anchoring motif

Translation

Translation is the process of protein synthesis in which the genetic information encoded in mRNA is translated into a sequence of amino acids on a polypeptide chain

- Ribosomes bind to mRNA in the cytosol and read the sequence in triplets of bases called codons (beginning with a start codon: AUG)

- Anticodons on tRNA molecules align opposite specific codons according to complementary base pairing (e.g. AUG = UAC)

- Each tRNA molecule carries a specific amino acid (according to a set of rules known as the genetic code)

- Ribosomes catalyse the formation of peptide bonds between adjacent amino acids (via condensation reactions)

- The ribosome moves along the mRNA molecule synthesising a polypeptide chain until it reaches a stop codon

- At this point translation ceases and the polypeptide chain is released (and can then fold into a functional protein)

- Multiple ribosomes can translate an mRNA transcript simultaneously (this group of ribosomes is called a polysome)

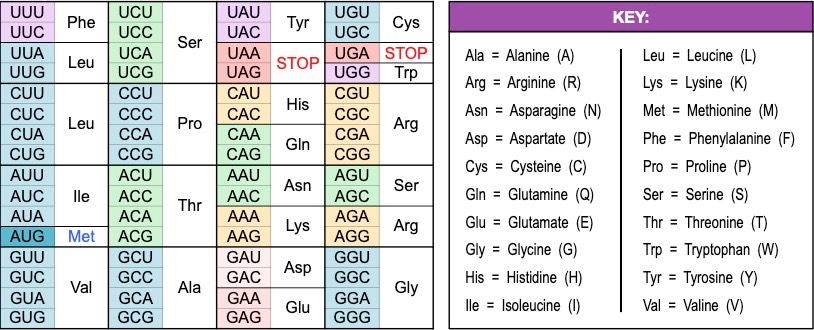

Genetic Code

The genetic code is the set of rules by which the information encoded within an mRNA sequence is converted into an amino acid sequence (i.e. polypeptide) by a living cell

- Codons are triplets of bases which encode for particular amino acids

- As there are four nitrogenous bases in RNA, there are 64 different codon combinations (4 x 4 x 4 = 64)

- The order of the codons will determine the amino acid sequence for a polypeptide chain

- Translation always begins with a START codon (AUG) and terminates with a STOP codon

The genetic code has the following features:

- It is universal - every living organism uses the same code (there are only a few rare and minor exceptions relating to viruses)

- It is degenerate - there are only 20 amino acids but 64 codons, so more than one codon may code for the same amino acid

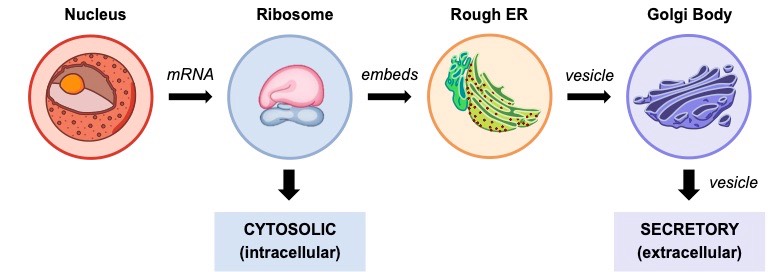

Protein Destinations

Protein synthesis can occur at one of two locations within the cell depending on the function of the protein being produced

- Free ribosomes will synthesise cytosolic proteins that are required for use within the cell (i.e. intracellular proteins)

- Ribosomes bound to the rough ER will synthesise proteins that are destined for external use (i.e. extracellular proteins)

In the protein secretory pathway:

- Polypeptides synthesised within the rough ER will be packaged into a vesicle and transported to the Golgi apparatus

- The Golgi complex will potentially modify the protein (e.g. glycosylation) and then export it out of the cell via a vesicle (exocytosis)

- Proteins can either be secreted by the Golgi immediately (constitutive secretion) or stored for a delayed release (regulatory secretion)

- Proteins synthesised via this pathway can also be shuttled to other organelles besides the Golgi (e.g. mitochondria, lysosome, etc.)